Would you like to receive our quarterly Housing Market update in your mailbox?

Then sign up below! If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to reach out to Jasper and his team.

The Dutch Housing Shortage

The Dutch Housing Shortage<p><strong>The Netherlands currently has a housing shortage of 285,000 houses, according to ABF Research. The shortage is recognized by the government and is given high priority by basically all political parties. However, it is not solved easily. In this article we discuss how the housing shortage is determined, how we got here and the way forward.</strong></p>

<p><em>This article previously appeared in the </em><a class="" href="https://assets.ctfassets.net/wfy6dr2scndo/4gUyUIYvF3jeyCAJ7hqQN1/c8c40e9fffc458ac4538798a707f5cfd/Dynamic_Credit_Quarterly_Update_2021-Q1.pdf"><em>Dynamic Credit Quarterly Housing Market Update 2021-Q1</em></a><em>. Want to be the first in line to </em><a class="" href="https://ivng.maillist-manage.eu/ua/Optin?od=12ba7e122948&zx=14ac22b3ac&lD=17d56f91bc18611&n=11699f75179e439&sD=17d56f91bc1862b"><em>receive the next update by e-mail? Sign up here</em></a><em>.</em></p>

<h3>How is the Dutch housing shortage calculated?</h3>

<p>The Dutch housing shortage is estimated as the difference between the number of households that need a house (housing demand) and the number of available houses (housing supply). Housing demand is mostly defined by households that:</p>

<ul><li>share a house with other households; and</li><li>reside in objects not meant for permanent residency, such as office buildings or recreational parks.</li></ul>

<p>A share of these households resides in these “alternative” accommodations as they cannot find an (affordable) regular house. Houses with households up to 25 years of age are excluded as these are usually students sharing a house, which is generally their preferred solution.</p>

<p>Future housing needs are estimated using the expected changes in households as a consequence of immigration, changes in demographics and changes in household size.</p>

<h3>How did we get here?</h3>

<p>These are the most important underlying factors of the Dutch housing shortage:</p>

<h4>Faster growth of number of households</h4>

<p>The future growth of the number of households was consistently underestimated through time, mainly caused by higher population growth due to more than expected immigration. In 2010 for example, it was estimated that the Netherlands would have 17.8 million citizens in 2040. As of 2020, this estimation was adjusted to 19 million. Some of the historical forecasts performed by the CBS are shown in Figure 2 together with realized values. These prognoses have been frequently adjusted upwards. Also estimating the (decreasing) household size over time has been challenging further contributing to a faster growth in households.</p>

<h4>Cyclical behaviour</h4>

<p>The Great Financial Crisis had a negative impact on the construction sector in the Netherlands: many construction and development plans were scrapped because confidence in the owner-occupied housing market was at a low, despite a growing population. According to the CBS in 2013 the number of newly built properties that were added to the housing stock was almost 49% lower than in 2009, the year with the highest number of newly built properties since 2000. Consequently, 5,000 construction companies ceased to exist, and many construction workers found employment in other sectors. Currently the number of construction workers is still not at the pre-crisis level (<a class="" href="https://www.trouw.nl/economie/zo-kwam-nederland-aan-een-tekort-van-331-000-woningen%7Eb04d8d53/">Trouw</a>). This shortage increases the costs of the building projects but also causes more delays.</p>

<p>“The main threats to increasing the pace of construction are environmental regulations in relation to nitrogen and PFAS, bureaucracy and lack of capacity at construction companies.”</p>

<p>Following the pandemic, cyclical behavior is showing again: some building projects in Amsterdam-Zuidoost are being postponed due to municipal budget cuts (<a class="" href="https://www.parool.nl/amsterdam/dit-jaar-geen-nieuwe-bouwinitiatieven-meer-in-zuidoost%7Ebc5a8062/#:%7E:text=De%20gemeente%20Amsterdam%20neemt%20in,de%20gevolgen%20van%20de%20coronacrisis.">Parool</a>).</p>

<h4>Housing corporations</h4>

<p>Dutch housing corporations traditionally played an important role in building affordable housing. Between 1945 and 1970, two million houses were built by these corporations. During this period the housing corporations were largely controlled by the government. The government planned where houses would be constructed, provided subsidies and loans. From 1990 onwards, housing corporations became gradually more independent to create a level playing field and with the expectation that they would become more efficient when liberalized.</p>

<p>However, in the first part of the 21st century, several corporations were involved in scandals such as construction fraud, excessive remuneration, risky investments and expensive interest rate derivatives. This has caused tightening of regulation for housing corporations and closer supervision.</p>

<p>In 2013, the government introduced a landlord levy for social housing (“verhuurdersheffing”) with the purpose to decrease the Dutch government budget deficit. To cover the costs of the landlord levy, social housing corporations were allowed to increase rents above inflation and increase rents further for tenants with higher incomes. After introducing this levy, the number of houses built by the corporations decreased by half, from 30,000 to 35,000 a year to approximately 15,000 a year in the years thereafter, further increasing the housing shortage.</p>

<h4>Decentralization</h4>

<p>In the year 2001 the provinces and municipalities in the Netherlands became responsible for deciding on building projects in their respective geographical areas. The idea was that the Netherlands was “finished” and the municipalities could do the “finishing touches”. However, in 2020, the Minister of the Interior and Kingdom Relations decided it was time to take the matter back into the hands of the national government, as a lack of coordination has been preventing a ramp-up in construction.</p>

<h3>The way forward</h3>

<h4>New construction</h4>

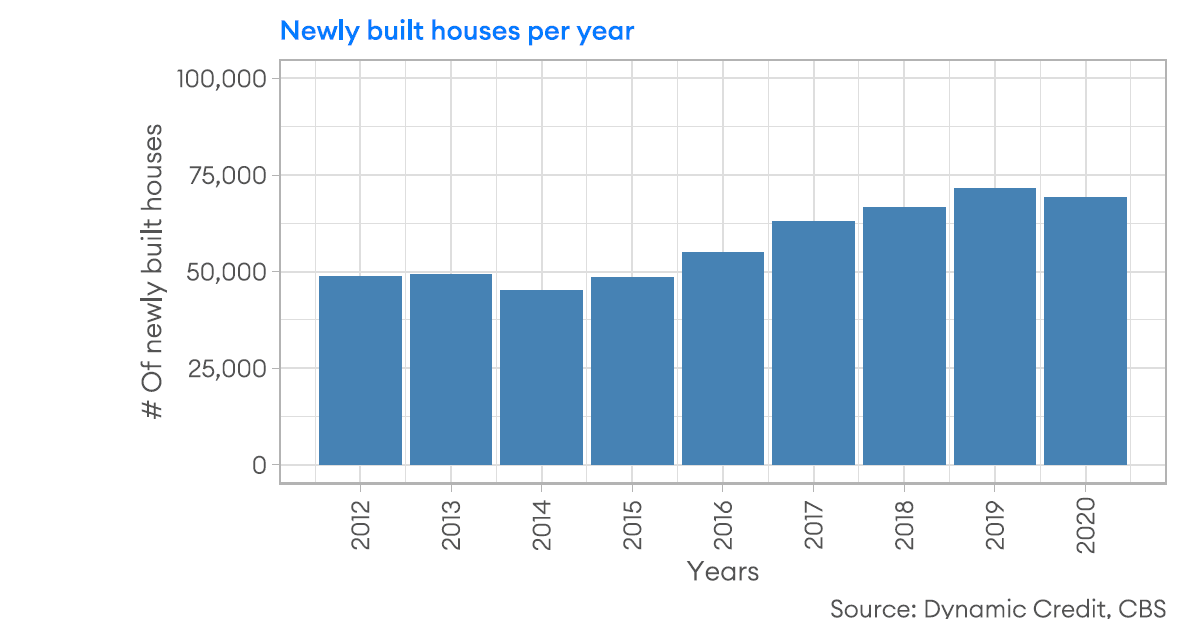

<p>An obvious solution is constructing more houses. The Minister of the Interiorand Kingdom Relations stated that between 2020 and 2030, one million new houses must be built (<a class="" href="https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/actueel/nieuws/2021/02/18/tweede-ronde-woningbouwimpuls-zorgt-voor-bijna-45.000-nieuwbouwwoningen">Rijksoverheid</a>). This translates to 100,000 new homes every year. The realization of this plan will prove to bequite challenging if we look at the newly built houses in the last years (Figure 3). Nonetheless, the average price of a newly built house is EUR 411,000, which is much more than the average first time buyer can afford.</p>

<p>In 2020, 69,000 houses were built and even though we see an upward trend over the past couple of years, reaching 100,000 per year will be very difficult given the current circumstances. Furthermore, it is uncertain whether more centralization will indeed increase the construction pace. The main threats to increasing the pace of construction are environmental regulations in relation to nitrogen and PFAS, bureaucracy and lack of capacity at construction companies. Recently new legislation has come into effect where environmental organizations and local residents can object against building projects even after the consultation rounds, which adds to the complexity. This is expected to further slow new building projects down.</p>

<h4>Transformation</h4>

<p>Another solution is the transformation of office buildings and shops into houses. According to CBS, 13% of all additions to the housing stock consisted of such transformations in 2019. It is expected that demand for office buildings and shops will not return to the prepandemic level, as working from home and online shopping are expected to persist. The province North-Holland, for example, estimates the number of potential additional houses as a result of transforming empty shops to triple to 21,000-27,000 due to the pandemic (<a class="" href="https://www.noord-holland.nl/Actueel/Archief/2021/Maart_2021/Ombouw_lege_winkels_maakt_meer_dan_20_000_woningen_mogelijk#:%7E:text=Ombouw%20lege%20winkels%20maakt%20meer%20dan%2020.000%20woningen%20mogelijk,-10%20maart%202021&text=De%20provincie%20Noord%2DHolland%20wil,de%20transformatie%20van%20leegstaand%20winkelvastgoed.">Provincie Noord-Holland</a>).</p>

<p><strong>Disclaimer</strong> Dynamic Credit Partners Europe B.V. (‘Dynamic Credit’) is a registered investment company (beleggingsondernemingsvergunning) and a registered financial service provider (financiëel dienstverlener) with the Dutch Authority for the Financial Markets (Autoriteit Financiële Markten). This presentation is intended for informational purposes only and is subject to change without any notice.The information provided is purely of an indicative nature and is not intended as an offer, investment advice, solicitation or recommendation for the purchase or sale of any security or financial instrument. Dynamic Credit may in the future issue, other communications that are inconsistent with, and reach different conclusions from, the information presented herein. Dynamic Credit cannot be held liable for the content of this presentation or any decision made by a third party on the basis of this presentation. Potential investors are advised to consult their independent investment and tax adviser before making an investment decision. An investment involves risks. The value of securities may fluctuate. Past returns are no guarantee for future returns.</p>

Then sign up below! If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to reach out to Jasper and his team.